A strange beauty lingers in the moment before the scalpel touches skin—the pulse of life, raw and unguarded, reveals more about humanity than the most intimate of moments. In that breathless pause, the body becomes something more than anatomical. It becomes metaphor, artifact, and threshold...

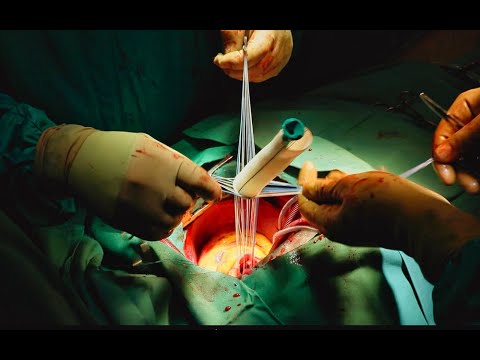

I recently watched a full recording of the Bentall Procedure, a surgery in which the aortic root, aortic valve, and part of the ascending aorta are removed and replaced—usually to correct a life-threatening aneurysm or congenital defect. ("Do you always do that?" the reader asks tentaively... to which the writer of this article does not respond.) At first, the body is intact. The chest rises and falls. The skin is untouched. Yet beneath that stillness, the heart beats audibly, visibly, like a secret trying to break free. That moment—before any incision—is strangely sacred. The patient is alive, autonomous, whole.

And then, the body is opened.

The sternum is sawed apart. The ribcage is retracted. Layers are pulled back to reveal the heart itself, thudding inside the opened chest cavity. Its movement is foreign and visceral—a muscular organ, pink and glistening, pulsing with terrifying vulnerability. It was at this moment I wondered how someone could ever stab another human in the heart—how such intimate violence is even possible. It terrified me to think that what requires a machine to repair and revive can be destroyed by human hands alone. This is the dark mirror of vulnerability: the realization that our deepest centers can be wounded not by accident, but by intent. As Levinas once said, “The face of the Other in its mortality summons us to responsibility.” And yet, we are reminded—over and over—that to be alive is also to risk being harmed by those who hold that responsibility in their own fallible hands. Anyway...

Eventually, the beating stops.

The surgeons sever connections, detach vessels, and insert tubes. A heart-lung machine takes over. Blood now flows through plastic and metal. The patient’s survival depends entirely on human design and human decision. Here, the body is no longer self-sustaining. It is suspended in a kind of mechanical purgatory.

This liminal state evokes Foucault’s theory of the body as a site of discipline and power. In surgery, the body becomes a canvas upon which we inscribe authority—scientific, technological, and philosophical. Freud saw the body as the original source of anxiety, full of instincts and unresolved trauma. Kant, always the rationalist, described the body as the boundary between our internal thoughts and the outside world. But I’m not a philosopher—I’m just an English and Communications student, trying to make sense of something that feels bigger than language. I don’t want to simply repeat what these thinkers said; I want to understand what they meant. And what I think they were getting at is this: in the surgical moment, all those neat categories fall apart. The body isn’t just something we live in or observe—it becomes a battleground where control, vulnerability, identity, and meaning all clash at once. It's no longer just a boundary. It’s the place where everything we believe about ourselves is put to the test.

Literature has long understood this. In Gothic and Romantic works, the body is where horror and beauty collide. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein gives us a creature built from death, revived through science, rejected by society. Edgar Allan Poe, who claimed that “the death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world,” fixated not just on death, but on the strange allure of stillness, decay, and violated beauty. In stories like Berenice, the narrator becomes obsessed with the teeth of his dying cousin—not her soul, but a part of her body, disembodied. And in The Imp of the Perverse, he explores the terrifying idea that we are drawn toward the very acts we know to be wrong, as if some secret self wills our undoing.

I’m no expert, but I think these stories echo something essential about surgery: that there is something both mesmerizing and deeply unsettling in seeing a body made vulnerable—not through violence, but through intention. Surgery, paradoxically, mirrors these themes. The body is opened not to destroy, but to heal—and yet in that moment, it is helpless, exposed, and sublime. It makes me wonder if the same fascination that drew Poe’s characters toward madness is also present—quietly—in the sterile theater of the operating room. And if so, what does that say about us? And, perhaps more awkwardly… what does that say about me, the writer who chose to spend a perfectly normal afternoon thinking about all of this? Anyway...

To witness the heart outside the realm of metaphor is to confront the fragile boundary between the physical and the symbolic. The exposed body—pulsing, bleeding, trembling—is not merely biological; it is epistemological, poetic, and existential. Surgery reminds us that flesh carries meaning, that death is not the end of narrative but a threshold—a line that feels absolute only in hindsight. When the heart is stilled and restarted by human hands, we are forced to reconsider: is life defined by the rhythm of blood alone? Or does something essential slip away in that quiet interval, when the body is opened, its center silenced, and then mechanically revived?

In that suspended moment—between silence and heartbeat, flesh and machine—we are asked not only how we survive, but what it truly means to be alive.